Disclaimer: This is one writer’s attempt to sum up and introduce collegiate women’s hockey. Information is subject to bias and opinion and can (and should) change. Please don’t consider this the be-all, end-all, but simply a starting point on learning the game.

The original version of this post was published in 2015 and it has been updated in 2025.

Before there was professional women’s hockey, there was NCAA collegiate hockey. Nearly 90% of the women lacing up their skates in the PWHL this season got their start in NCAA collegiate hockey.

Whether you’re a new women’s hockey fan, or you love the pros but have never delved into the college waters, here’s a primer that should help you better understand.

History

There are currently 41 women’s collegiate hockey teams.

Women’s ice hockey was an officially sanctioned NCAA sport in the 2000-2001 season, but the roots of collegiate hockey go back 35 years from there. Women’s collegiate hockey started long before it was NCAA-sanctioned. Brown University had the first team in 1965. The first Ivy League tournament happened in 1976. The ECAC had their first tournament in 1984.

Women’s ice hockey became an Olympic sport in 1998. There was no formal league or plan in place in the US to train and develop players. During the 1997-1998 season, the American Women's College Hockey Alliance was born, and it was financed by the US Olympic Committee. That original league held their own National Championships in 1999 and 2000, which were won by Harvard and Minnesota. Those championships are generally not counted when talking about national titles won by a university – only NCAA Championships.

NCAA Championships

Early on, the NCAA was dominated by the University of Minnesota-Duluth (UMD), who won the first three national championships and have five total. Harvard, Brown and St. Lawrence were among the early powerhouses – these schools had hosted “club” level hockey for many years before turning it into a sanctioned intercollegiate sport. Wisconsin has the most titles with seven.

2001 National Champion: UMD

Runner Up: St. Lawrence

2002 National Champion: UMD

Runner Up: Brown

2003 National Champion: UMD

Runner Up: Harvard

2004 National Champion: Minnesota

Runner Up: Harvard

2005 National Champion: Minnesota

Runner Up: Harvard

2006 National Champion: Wisconsin

Runner Up: Minnesota

2007 National Champion: Wisconsin

Runner Up: UMD

2008 National Champion: UMD

Runner Up: Wisconsin

2009 National Champion: Wisconsin

Runner Up: Mercyhurst

2010 National Champion: UMD

Runner Up: Cornell

2011 National Champion: Wisconsin

Runner Up: Boston University

2012 National Champion: Minnesota

Runner Up: Wisconsin

2013 National Champion: Minnesota

Runner Up: Boston University

2014 National Champion: Clarkson

Runner Up: Minnesota

2015 National Champion: Minnesota

Runner Up: Harvard

2016 National Champion: Minnesota

Runner Up: Boston College

2017 National Champion: Clarkson

Runner Up: Wisconsin

2018 National Champion: Clarkson

Runner Up: Colgate

2019 National Champion: Wisconsin

Runner Up: Minnesota

2020 National Champion: Tournament cancelled due to COVID

2021 National Champion: Wisconsin

Runner Up: Northeastern

2022 National Champion: Ohio State

Runner Up: Minnesota Duluth

2023 National Champion: Wisconsin

Runner Up: Ohio State

2024 National Champion: Ohio State

Runner Up: Wisconsin

Minnesota also owns a title that may never be surpassed. They went undefeated over the 2012-2013 season and had a 62-game unbeaten streak from February 17, 2012 to November 17, 2013. It’s the longest streak in collegiate hockey, either men’s or women’s. They won back-to-back national titles over the stretch.

It’s an incredible feat.

Patty Kazmaier Award

The Patty Kaz is given to the top female collegiate player every year. The award is named in honor of the late Patty Kazmaier-Sandt, a four-year varsity letter winner for Princeton from 1981 through 1986, who also played field hockey and lacrosse. Patty died on February 15, 1990 at the age of 28 from a rare blood disease.

An award of the USA Hockey Foundation, the process for selecting the winner starts with coaches nominating players for the award. Players who were nominated by multiple coaches are placed on an official ballot, which was returned to the coaches to vote for the ten finalists. From there, a 13-person selection committee made up of NCAA Division I women's ice hockey coaches, representatives of print and broadcast media, and an at-large member and representative of USA Hockey have a conference call to discuss each finalist and then vote, ranking their top three picks. Those votes are tallied to determine the winner.

Harvard leads all schools with six Patty winners, followed with Wisconsin with five.

1998 Brandy Fisher - New Hampshire

1999 A.J. Mleczko - Harvard

2000 Ali Brewer - Brown

2001 Jennifer Botterill - Harvard

2002 Brooke Whitney - Northeastern

2003 Jennifer Botterill - Harvard

2004 Angela Ruggiero - Harvard

2005 Krissy Wendell - Minnesota

2006 Sara Bauer - Wisconsin

2007 Julie Chu - Harvard

2008 Sarah Vaillancourt - Harvard

2009 Jessie Vetter - Wisconsin

2010 Vicki Bendus - Mercyhurst

2011 Meghan Duggan - Wisconsin

2012 Brianna Decker - Wisconsin

2013 Amanda Kessel - Minnesota

2014 Jamie Lee Rattray - Clarkson

2015 Alex Carpenter - Boston College

2016 Kendall Coyne - Northeastern

2017 Ann-Renée Desbiens - Wisconsin

2018 Daryl Watts - Boston College

2019 Loren Gabel - Clarkson

2020 Élizabeth Giguère - Clarkson

2021 Aerin Frankel - Northeastern

2022 Taylor Heise - Minnesota

2023 Sophie Jaques - Ohio State

2024 Izzy Daniel - Cornell

As shown by the number of Olympians on the above list, the strength of competition in NCAA hockey has developed some of the top talent in the world. While the top US-born talent has long been culled from the NCAA, international players are now turning to the league as the best place to train, learn, and develop. At the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics, just eight members of Team Canada had played in the NCAA. By 2014, every member of the US team in Sochi and 14 of the 21 Canadian skaters were current or former NCAA players. At the 2022 Beijing Olympics, all but one player from US and Canada were current or former NCAA players.

An early strategy used by UMD’s coach Shannon Miller was to recruit top talent from outside the United States. The draw of a degree, combined with stellar training facilities and top-tier coaching, was an enticing one. At the 2006 Turin Olympics, there were 22 players with NCAA experience on rosters other than the US or Canada. Fifteen of those players had played at UMD. The other seven represented just five other schools

It was an effective recruiting strategy for a smaller school that may not have the appeal or draw of large universities like Minnesota or Harvard. It was so successful that other small programs began looking outside North America for top talent. And conversely, players from Europe and Asia look to the NCAA as a place to grow and develop in ways that aren't available to them in their home countries.

At Sochi in 2014, there were 26 players on rosters other than US and Canada that had NCAA experience, and they represented nine different schools. In Beijing in 2022, there were more than 60 players on other countries' rosters who'd played for more than two dozen different schools.

Organization

If you’re familiar with the format of college hockey, go ahead and skip to the next bold heading.

One of the first things to know is that there are several small schools that play Division I hockey, despite the fact that their other athletic teams compete in Division II or III. That’s a rule that’s since changed with the NCAA - now if you have one team playing DI, they all have to play in the same division. But in both and men’s collegiate hockey, you'll see St. Cloud State and Union competing against Wisconsin, Harvard, and Minnesota.

There are five conferences in women’s hockey --and they do not align with other, traditional collegiate sports conferences.

Atlantic Hockey America (AHA) began this season after a merger of the women's only hockey conference CHA and the men's only hockey conference Atlantic Hockey.

Its current members are Lindenwood, Mercyhurst, Penn State, Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT), Robert Morris and Syracuse. University of Delaware has announced the formation of a team to join the AHA for the 2025-26 season.

The Eastern Collegiate Athletic Conference (ECAC) began sponsoring an invitational women's tournament in 1985. ECAC teams began playing an informal regular season schedule in the 1988–89 season, with the conference officially sponsoring women's hockey beginning in the 1993–94 season. Twenty-four different teams have called the ECAC home in their history. The only NCAA Championships not won by the WCHA belong to Clarkson, who won the title in 2014, 2018 and 2019.

The current members are Brown, Clarkson, Colgate, Cornell, Dartmouth, Harvard, Princeton, Quinnipiac, Rensselaer (RPI), St. Lawrence, Union, and Yale.

Hockey East (HE) began play in 2002. Several of the universities who had men's Hockey East programs were already supporting women's hockey teams and it became clear a women's conference was needed. If any of the HE member institutions add women's hockey, they will automatically be granted entrance to the conference.

The current members are Boston College, Boston University, Connecticut, Holy Cross, Maine, Merrimack, New Hampshire, Northeastern, Providence and Vermont.

The New England Hockey Alliance (NEWHA) began as a loose scheduling agreement among Sacred Heart, Post, Holy Cross, St. Michael's, St. Anselm, and Franklin Pierce in 2017 after several of them were removed from their Division III conference. Holy Cross went on to join Hockey East, but the other schools decided to adhere to Division I recruiting rules and offer scholarships in 2018 and NEWHA was approved as a Division I NCAA conference in September 2019.

NCAA rules required two years of play with the same six teams before the conference earned an NCAA Tournament auto bid. LIU earned the first NEWHA NCAA Tournament bid by winning the 2023 conference tournament. Stonehill joined the league in 2021 and Assumption joined in 2024.

The current teams are Assumption, Franklin Pierce, Long Island University (LIU), Post, Sacred Heart, Saint Anselm, St. Michael's, Stonehill

The Western Collegiate Hockey Association (WCHA) began sponsoring women’s hockey in the 1999-2000 season. Twenty of 23 NCAA championships have been won by members Minnesota, Wisconsin, Ohio State and UMD. The University of North Dakota was a member of the WCHA until they cut their women's program in March 2017. St. Thomas elevated their program to the DI level and joined the WCHA in 2021.

The current members are Bemidji State University (BSU), Minnesota State-Mankato (MSU), University of Minnesota, University of Minnesota-Duluth (UMD), Ohio State, St. Cloud State (SCSU), St. Thomas and Wisconsin.

Rules - AKA There is no checking in women’s hockey

The biggest difference between men’s and women’s hockey is that women’s hockey has no body-checking -- but don’t let that confuse you into thinking that this is going to be a non-contact game.

You can download the full NCAA hockey rules book here.

There is just a single rule in the book that pertains only to the women’s game. Rule 94.

Rule 94 - Rules for Women’s Ice Hockey

94.1 Rules for Women’s Ice Hockey - The following rules are to be used for women’s ice hockey competition:

94.2 Body Checking - Body checking is not permitted in any area of the ice. Body checking occurs when a player’s intent is to gain possession of the puck by separating the puck carrier from the puck with a distinct and definable moment of impact.

PENALTY—A minor, major or disqualification, at the discretion of the referee.

94.3 Angling - Angling is permissible. Angling is a legal skill used to influence the puck carrier to a place where the player must stop due to a player’s body position.

94.4 Incidental Contact - Incidental contact, when two players collide unintentionally, may occur.

Though checking is a penalty on the women’s side, you’ll still see plenty of contact. In fact, you’ll see players run each other over, hit the ice, and hit the boards, and generally think to yourself "that’s not a check?" The simple answer is that yeah, it probably was. That’s one of the arguments in favor of making checking legal. Every ref calls the rule differently and it is subjectively interpreted. Regardless of the interpretation of checking, it is legal for the players to use their bodies to their advantage. Both the SDHL (Swedish professional league) and the PWHL have rules to allow for some body contact.

I expect this rule will continue to evolved, but count me as someone who doesn't want full contact and open-ice hitting in the women's game.

Women’s hockey is, first and foremost, a game of finesse. Since players can’t just knock each other over to win the puck, they have to employ skill and dexterity to get through a zone and beat a defender. You’ll see a lot more fancy puck-handling, toe drags, and dangles. To me, to love the game of hockey is to love fast skating, crisp play, and pretty passes, and the lack of hitting in the women’s game actually brings you more of those things than in the men’s game. I do not need or want women's hockey to be like men's hockey.

Postseason

Each conference has a different format for their postseason tournament. Refer to the our conference explanation pages, linked below, for the details on how each of them determines a champion and winner of their auto-bid.

AHA

ECAC

Hockey East

NEWHA

WCHA

NCAA Tournament

In 2021, the field for the NCAA Tournament was expanded from eight to 11 teams. Yes, 11 is a stupid and arbitrary number (read my thoughts on that here). The top five teams are seeded and the rest of the bracket is filled in from there.

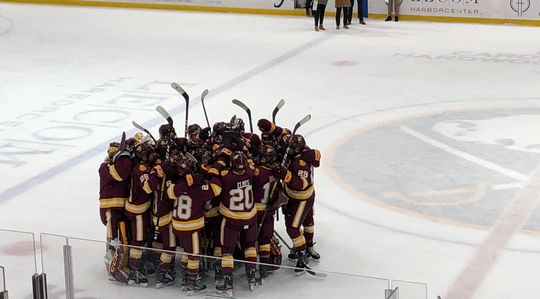

For visual reference, this is the 2024 NCAA Tournament bracket:

Each of the five conferences receive an auto-bid into the NCAA Tournament. The team that wins each conference’s postseason tournament receives that bid. The other six spots are assigned based on Pairwise rankings. Pairwise Ranking (PWR) is a system which attempts to mimic the method used by the NCAA Selection Committee to determine participants for the NCAA National Collegiate Women's hockey tournament.

The NCAA switched from the use of RPI (Ratings Percentage Index) to NPI (NCAA Percentage Index) in 2023. NPI is calculated based on winning percentage and the opponent’s NPI rating itself, which is intended to provide a more accurate gauge of strength of schedule and much simpler and cleaner math. A quality win bonus (QWB) is awarded for a victory or overtime loss against a team with an NPI of 51.5 or better.

To simplify it somewhat, think of each game a team plays as having its own NPI. A team’s season NPI is the average of all of those NPIs together. As with the RPI, “bad wins” (wins that would hurt a team’s ranking) are removed and QWBs from “bad wins” that have been removed are not added. Wins that would lower a team’s NPI are removed and the average is calculated using the remaining number of games as the denominator.

A team's final NPI number is the calculation of 25% of the winning percentage and 75% of their opponents NPI plus their own QWB for each game. That number is what’s divided by the number of counted games to get a team's NPI.

The PWR compares all teams by these criteria: record against common opponents, head-to-head competition, and NPI. For each comparison won, a team receives one point. The final PWR ranking is based on the number of points (comparisons) won against teams under consideration. Ties are settled by the NPI.

Miscellaneous

Check out all of Victory Press' NCAA primers