We love to talk about “growing the game.” It’s a catchphrase -- and the main directive behind almost all change and development in women’s hockey at this point.

Why are there two pro leagues? Why was it important to play in the Winter Classic? Why is supporting the U-18 and U-22 teams important? Why is having more college hockey teams important? Because we want to “grow the game.”

The phrase has been bandied about so much lately that at times it loses meaning. Are we talking about higher youth enrollment numbers? High attendance at college or pro games? More medals at international tournaments? Televising games?

If this is the fundamental imperative of our sport, what constitutes success at “growing the game”? Is there ever a point where a sport or league stops trying to grow the game? Isn’t Major League Baseball also still trying to get more fans? Make more money? "Grow the game"?

When current US Women’s National Team goalie Jessie Vetter, 30, was coming through USA Hockey’s youth development, there was no U-18 team. Team USA’s U-18 squad is currently playing in the IIHF U-18 Women’s World Championships.

Katie King Crowley, coach of the women’s hockey team at Boston College, played on the first ever U.S. Olympic women’s ice hockey team, winning the gold medal in Nagano. She won silver in 2002 and bronze in 2006. She was the 2006 USA Hockey Bob Allen Player of the Year. In 2007, she became the head coach at Boston College.

She jokes that she has horrible timing, as the U-20 and U-22 national development teams were all created the year after she aged past eligibility for them.

Those are obvious and tangible signs that the women’s game has grown and improved over the past 18 or so years, but what about the college game?

When women’s college hockey was introduced as a Division I sport for the 2000-2001 season, there were 22 programs. The 2015-16 season kicked off with 36 teams, with four of them having been added over the past four seasons.

Perhaps the biggest sign of any advances and changes in the women’s college game came with Clarkson winning the 2014 National Championship. They remain the only non-WCHA team to win the title. Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Minnesota-Duluth have combined to win the other 14 titles.

But Brad Frost, women’s hockey coach at the University of Minnesota, said there’s no better time to become a women’s hockey fan. The level of play, the pace of play, and the style of players give the sport a depth that didn’t exist just a decade ago.

“There's no question. If you haven’t watched women’s hockey in 10 years, you’ve got to go out and give it a chance. You’re going to be very surprised by the caliber of players.”

After “grow the game,” there’s no other word more often used when talking about women’s hockey than “parity.” Whether it’s talking about unseating perennial favorites in the NCAA, or teams challenging USA and Canada on the international scene, finding a way to lessen the gap between the haves and have-nots in women’s hockey is a priority. It's not possible to grow the game without it.

And while teams like Minnesota, Wisconsin and Boston College have continued to dominate the top of the polls over the past few years, there’s a much smaller gap between the top few teams and the rest of the polls. As Scott Spencer, head coach at Lindenwood said, there’s very little separating the teams ranked at no. 4 to no. 15.

“Right now, I think the majority of the top-end kids are going to two or three programs, but the separation from the top-end kid to the second-tier kid is smaller and I think programs are doing a better job of identifying those kids, instead of wasting their time on the next Olympian. They’re finding the girl that’s just underneath that and going hard after them, and that’s helping the parity for sure. I don’t see a giant separation from four on. I think it’s awesome. Colleges and universities are doing a better job of hiring the right people for the job,” said Spencer. “When I first started, there were probably eight teams and then the rest. I think it’s now 15-20 deep. It still needs to get better, but I think the gap has closed drastically.”

With teams like Lindenwood, Bemidji State, and St. Cloud State showing immense growth, both in the number of wins on their schedule and in the players on the ice, the talk of parity in college hockey has increased -- mainly that there may finally be some.

To a person, every source for this piece pointed to the increased number of players having an impact on the quality of play in women’s college hockey. Not only is the talent pool larger, but it’s much more talented -- which has made a world of difference in women’s college hockey.

Wisconsin coach Mark Johnson has been with the program since its third season and coached Team USA at the Vancouver Olympics.

“A big thing that’s changed in the past four or five years is the depth of college hockey on the women’s side. Years ago, some teams had a good player, or a couple of good players. The good teams had a few more good players, but now everyone’s equipping themselves with good players and the depth of it is that teams can play three lines. Some teams can play four lines and have two goaltenders that can compete. So that overall base of depth for teams has increased quite a bit...Teams have good players and as we see on the scoresheet every weekend, the surprises that we might [not have] thought about five or six years ago don’t surprise anybody. We talked seven or eight years ago about the same thing; we wanted parity and we wanted this competitive atmosphere, and it’s better for our sport to have that,” said Johnson.

Spencer, who was an assistant at Robert Morris starting in 2006, puts it bluntly.

“There’s kids I had at Robert Morris that couldn’t play Division I hockey today. And they played four years of Division I. That’s not a knock on those kids, it just speaks to how many more better players there are out there now,” he said.

Crowley also offered the flip side of that observation, pointing out that she often has to turn down players that she knows would have made the roster of top teams just a few years ago.

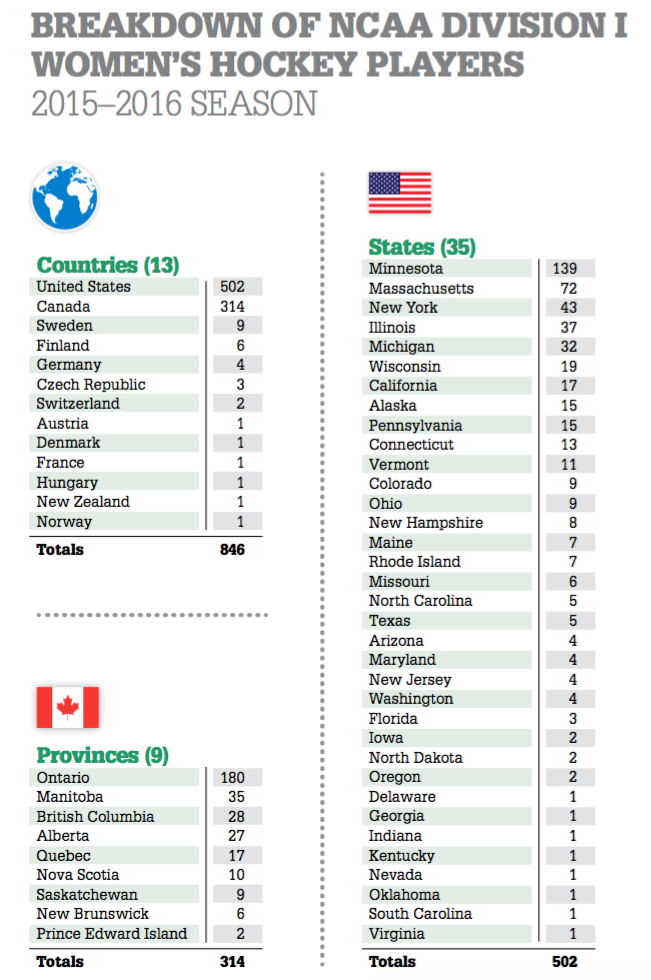

This dynamic is playing out in Minnesota, as well. While there’s always been a greater number of players coming from the state, Frost estimated that the number has doubled over the past decade.

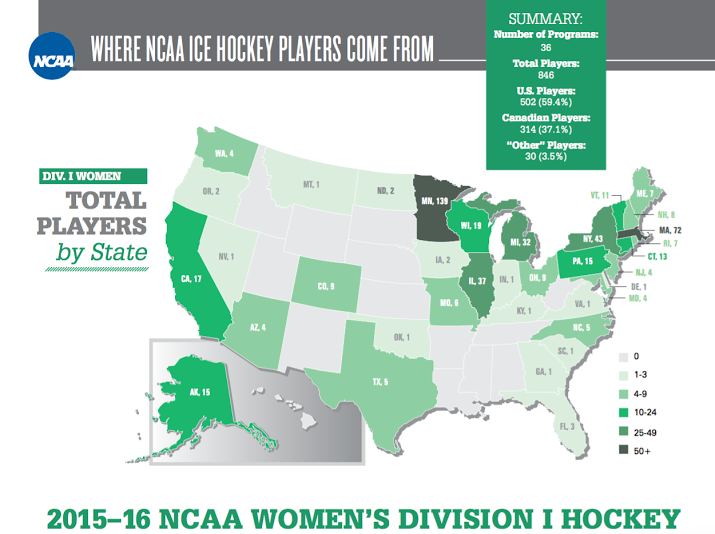

Not only are there more players, but they are coming from all across the country, said Crowley. With kids having grown up playing roller hockey that transition to the ice, there's a wide-open opportunity for kids in every state.

“Obviously there’s more players playing, but you also notice that there’s more players playing all over the United States,” said Crowley. “Women’s hockey has reached all parts of the US, never mind internationally. You look at rosters, there’s people from California, there’s people from Texas, there’s people from Arizona -- random places that you wouldn’t have found women’s hockey players in the past.”

Having representation and the ability to see girls “just like them” go on to play in college or on the national team is one of the crucial parts of growing the game. With little to no TV representation, giving young girls access to players and games is incredibly important.

Wisconsin’s Johnson has made a point of bringing the college game to previously under-served areas for years now. In conjunction with other coaches and programs and with USA Hockey, the Wisconsin women’s hockey program has played games in Vail, Colorado; San Jose, California; Fort Myers, Florida; and Lakewood, California.

“If you can expose people, whether it’s on television or whether it’s them coming to a game, that’s one of the keys to growing the sport. We’ve been fortunate that we’ve been able to do that; put on clinics and our players get a chance to go on the ice with young girls that are playing in areas that don’t have college hockey. It sparks interest,” said Johnson.

There are gives and takes that come from players growing up playing with all girls or growing up having played on boys' or mens' teams. Johnson pointed to Nikki Burish, who was such a strong player that she played on an elite boys high school team, as well as the team’s current goalie, Ann-Renée Desbiens, who played against 19- and 20-year-old men in Quebec. Both players had to transition to a much slower and less physical women’s game.

While both Frost and Johnson had positive things to say about what girls can learn from playing with boys' teams in their youth, Frost also mentioned the negative experiences of being isolated in other locker rooms and getting picked on.

Most importantly, though, Johnson pointed out how little the talent level of players has changed, regardless of how they played as youths.

“Certainly in the last six, seven, eight years, we've seen a lot more girls come into our programs that have played against only girls and we’ve yet to see a change in the skill level,” said Johnson.

In the 15 years of NCAA women’s Division I hockey’s existence, there has been massive growth in the development of youth girls players. Though we’re still at a point where many of the current crop of players grew up playing with boys, some up through college and juniors, all the coaches mentioned that they've seen more players who have had the opportunity to play girls' youth hockey.

Not only have both USA Hockey and Hockey Canada put an emphasis on growing the game, but initiatives like the IIHF’s Girls Hockey Weekend are helping put girls on the ice for the first time across the globe.

USA Hockey and Hockey Canada have worked to provide coaching training and get skilled coaches on the ice with the players. While 15 years ago, someone’s dad might have been coaching only because his daughter wanted to play, the youth level is full of prepared, invested coaches.

“It starts with the coaching. I think Hockey Canada and USA Hockey are doing a good job of giving younger coaches the tools to be able to develop kids at a younger age and help them to having the goals to have the tools to play on a U-18 team. That’s the nugget there for young kids to strive for,” said Spencer.

Additionally, Spencer points out, the pioneering wave of players who played in the first few Olympics and the first seasons of the NCAA are working their way into coaching positions. Not only do they provide inspiration and mentorship, but also, they’re the first generation of players who have been where the young girls are. That extra layer adds so much to their ability to coach them and coach them well, he said.

“The more kids that we can develop and make into Division I caliber hockey players -- they all can’t go to the same school. So eventually it will all catch up and it will spread out more, and I think I’m seeing that from my perspective,” said Spencer.

Showing two views on the same issue, Frost hypothesized that aren’t as many dominant players coming out of girls hockey as there were in previous years, but Spencer thinks that this might just be about perception.

“I hear some coaches talk about how there’s not as many top end players any more, and I’m like, is that it or is it that the separation isn’t as great and that second-tier kid -- there’s more of them, and it’s making it better hockey. Those top-end kids don’t stand out as much anymore,” said Spencer.

Spencer said it used to be that he’d walk into a rink as a recruiter and instantly be able to pick out the best player on the ice. There were usually one or two great kids on each team or at a tournament. But as the level of play increases across the board, the gap between elite players and those other players is so much smaller that it’s often more difficult to label a player as “elite.”

One area that every coach touched on was the strength of their goalies. On the East Coast, where the teams play throughout the week and in one game series, the ability for any team to beat another on any given night is a given. Crowley remembers a coach telling her the game may as well be called “goalie” for how much a hot or cold goalie can affect a game or a season.

Both Lindenwood, with Nicole Hensley, and Bemidji State, with Britni Mowat, have built their ability to upset teams on the back of a stellar goalie.

“We feel we have the best keeper in the country and if not, she’s certainly up there. That helps. If you have a good goalie, you can play with anybody. I think the talent base has broadened to the point where there are enough good players out there that if you get the right player and you can develop that culture and bring in that player that is not the star recruit that everyone’s going after, but if you can get a really good player with a great attitude that wants to be a part of your team, then you can have a chance and that’s what we preach here,” said Scanlan.

And while Crowley is in awe of the player growth and development she’s seen just from her playing days to having multiple national team or Olympic on the college team she coaches, there’s still a lot of room to continue to grow.

Last season, Boston College averaged just more than 400 fans per home game. Though there’s the ever-present argument about competing for people’s time and entertainment dollars in Boston, the fact of the matter is that just four teams averaged more than 1000 people per game in 2014-2015 -- Minnesota, Wisconsin, North Dakota and Minnesota-Duluth. There are 13 programs that average fewer than 300 fans per home game, and Brown, the oldest women’s hockey program in the country -- having put a team on the ice since 1964 -- averages fewer than 100 fans per game.

Note that the college bowling national championship will be televised, while the women’s hockey national championship will not.

Over the course of the fifteen-year history of women’s hockey as a Division I sport, there have been 150 spots in the season-ending USA Today poll. Five schools -- Minnesota, Wisconsin, Harvard, Minnesota-Duluth, and Mercyhurst -- have held 66 of those rankings. Five schools have owned 44% of the final spots.

Of the 22 girls on the U-18 team competing at the IIHF Women’s World Championships, 16 are from the state of Minnesota. That would appear to say positive things about girls' youth hockey development in Minnesota, though maybe it raises questions about youth hockey development elsewhere.

But both Frost and Scanlan independently brought up that there are places in Minnesota where the focus is off of girls' hockey. Enrollment numbers are down and schools are having to combine to field a full team, which is a bit concerning, at the very least. The Gophers have been dominant, other college programs in the state are experiencing unprecedented success, and the youth national team is stocked with Minnesota-bred talent, so a decrease in the focus on girls' youth hockey is disconcerting.

It’s easy to get disheartened by low attendance numbers, dropping enrollment figures, and lack of television or online streaming options for the game, but we have to remember that we’re fewer than 20 years removed from first competing in the Olympics and just 15 years removed from the first women’s college hockey season.

From those points, the growth and advancement in the game are apparent in both visible and intangible ways. As fans who want to see the sport succeed and have a larger impact, it’s easy to lose sight of that. But it’s all about perspective. The teams currently appearing on the polls are almost entirely different from the teams that dominated the sport in the early years.

“As long as we keep talking about it, and if everybody has the mentality of what’s best for the game and not what’s best for individual programs, I think we continue to keep growing,” said Spencer.

(Infographics in this post are from Stops & Starts: The Official Publication of the American Hockey Coaches Association, December 2015 Vol. XXIII, No. 2, via AHCAhockey.com)