When I was a kid, I was always taller than everyone else. When we had picture day at school, from kindergarten to grade eight, I was inevitably the one in the middle at the back of the class portrait who towered over the other kids.

The same was true of the sports I played as a kid, from soccer to softball to hockey. As I grew, I wasn’t just taller than everyone else, but bigger, broader, and stronger, too. I had an adult body that was playing kids’ games.

Even at a young age, my body and my gender were frequently a problem for others.

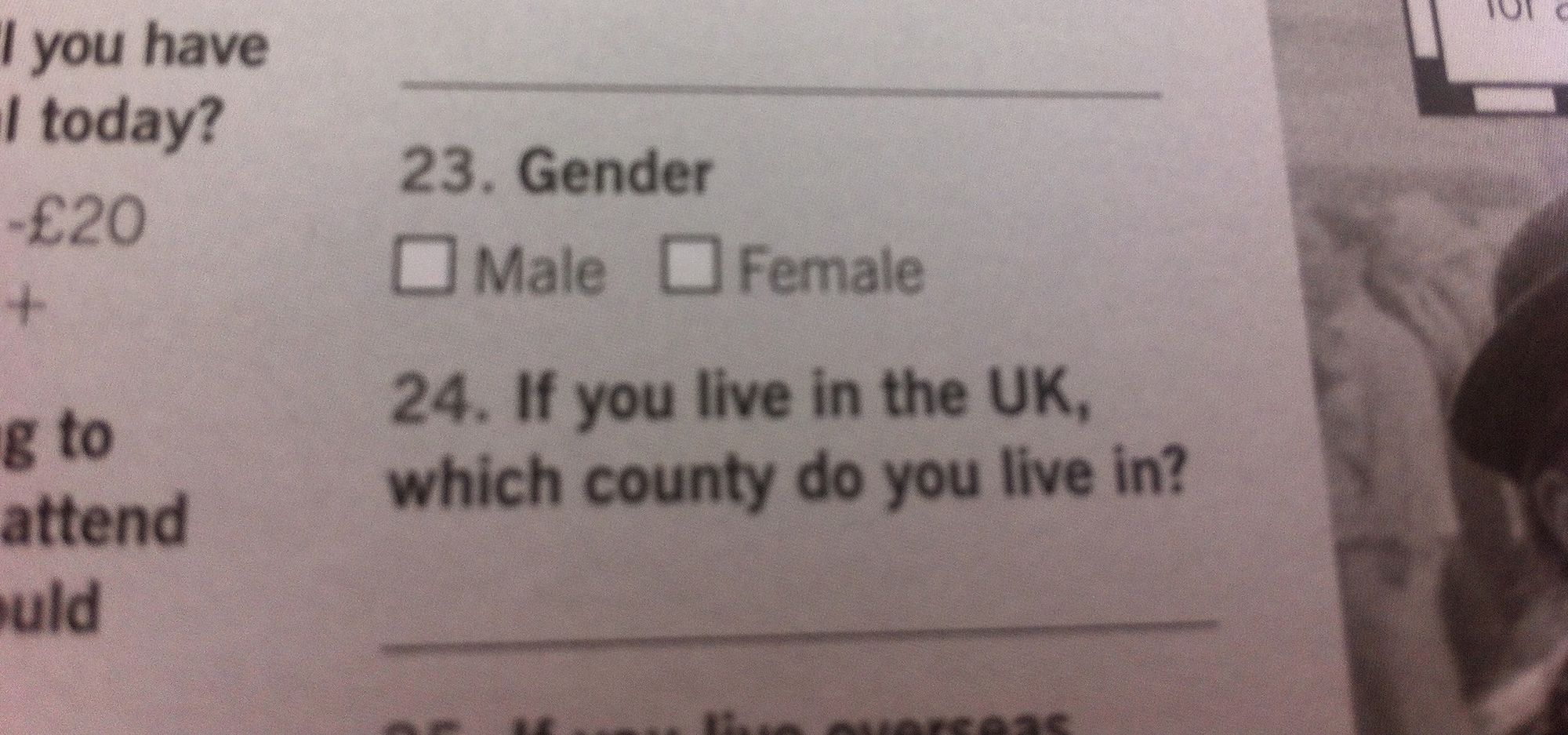

Whether I was in class or on a playing field, there was a constant, cutting question: are you a boy or a girl? Some of my earliest memories of school are being taunted with this question, accompanied by kicks and punches, being shoved into walls, or knocked down onto pavement.

In sports, this debate took a more pointed form. There were requests to see my birth certificate to prove that I was a girl amid the whispers, disapproving looks, and pointing. It didn’t help that I was actually quite good at the sports I played. When I played mixed-gender sports, the disbelief came from parents and coaches couldn’t believe that a girl was better—by a wide margin—than their sons at sports. When I played on girls’ teams in girls’ leagues, there were accusations of cheating that stemmed from my masculinity and my less evident femininity. What was clear in both sports and school was that the people around me had a narrow understanding of gender, and that neither my body nor my identity fit those definitions. This treatment prepared me for a life where trans people aren’t respected or valued.

Simply existing in my body and being myself as a kid was a problem for so many people…which meant that it was a problem for me.

This type of gender discrimination, this type of transphobia, has been with me all my life. For me, it didn’t begin when I started to vocalize that the gender I had been assigned at birth wasn’t right or when I eventually came out. It has been a constant in my life. I’ve learned that this type of behavior is rarely recognized for the discrimination that it is, and that this kind of violence seldom seen as transphobic. But in both cases, it was and it is.

The two spheres I inhabited as a kid (school and sports) left me feeling like I was strange, aberrant, or even unnatural. I was constantly told it would get better. It would be better in high school. It would be better in university. It would be better at work. It would be better when I had my own place. But it wasn’t.

The lie of "it gets better" is that for many of us, it doesn’t happen. Those words aren’t magic and they put a lot of onus for societal change on an individual who is suffering. Things didn’t get better in adulthood. The question simply evolved to: "Are you a man or a woman?"

The strict definition of gender I encountered in sports impacted the definitions of gender that I encountered elsewhere. We want so much for sports to be something separate, or even an escape, but they’re not. They’re not only a reflection of the society we live in, but they also shape that society by establishing normative cultural practices.

Before I was aware of what it would mean for my life, hockey was shaping my masculinity. I knew what type of player to be on and off the ice. Stand up for your teammates. Play through pain. Don’t celebrate; act like you’ve done it before. It wasn’t a good fit. Thankfully, the codes I heard about on intermission panels and during broadcasts didn’t fit the scenarios and dynamics I came across while playing girls’ sports. But at the same time, I didn’t know what to do with my masculinity; and no one had a good answer for why I couldn’t just be who I was.

Sports (like hockey) maintain a traditional gender binary, and professional leagues (such as the NHL) rely on it. This system deliberately leaves behind trans athletes and trans fans.

We want so much for sports to be something separate, or even an escape, but they’re not. They’re not only a reflection of the society we live in, but they also shape that society by establishing normative cultural practices.

The manufactured masculinity that has historically been part of the men’s game is crumbling. The moral codes, toughness, and brutality of the pre 2004–05 lockout NHL are increasingly seen as problematic. We debate the violence in hockey, head shots, and fighting in the men’s game, as well as body contact in the women’s game, with more frequency and resources than we discuss the violence that trans people face on a daily basis.

Now, it’s logical to discuss the dangers inherent in hockey violence and to subject those dangers to in-depth inspection. Careers, as well as individual health and well-being, are at stake. In the case of concussions, lives are being risked. Suspensions, lawsuits, and hockey culture hang in the balance. Hockey is entertainment, and entertainment matters a great deal in our society.

There is money to be won and lost here, too, in advertising dollars and settlement payouts...but there isn’t money to be won in trans violence.

On the surface, the violence that occurs on the ice at a hockey game doesn’t appear to have much in common with the violence to which trans lives are so often subjected. One is part of a game that’s subject to rules and codes of discipline: the other is a terrifying, constant threat to those who do not fit cisnormativity and one that almost always goes unpunished. Where the two converge is in the importance of the traditional gender binary. Trans identities undermine the rigidity of the gender binary, and the violence that trans people experience is in many ways an attempt to restore order. When we juxtapose the violence in hockey with violence experienced by trans people, we see that the most damaging code in sport is a strict adherence to traditional gender roles.

Mainstream professional sports in North America thrive on that strict adherence. Such an adherence allows a disproportionate amount of resources and media attention to be focused almost exclusively on men’s sports at the professional level. A traditional understanding of gender means privileging the cis male athlete, and correspondingly, the cis male fan. Those with power care almost exclusively about the cis male experience of both playing and watching sport.

This privileging is frequently positioned as a question of merit: there are biological differences between men and women, so the argument goes, which result in men being bigger, faster, and stronger, and consequently, better athletes. If fans are asked to pay for tickets, merchandise, and streaming packages, they want to see the best of the best. It’s not misogyny, but simply a meritocracy.

Except, of course, it isn’t.

Those who believe we pay attention to cis male athletes most simply because they merit it ignore the systemic advantages from which cis men benefit by creating and maintaining the power structures in both the sports world and in our society. We live in a violently misogynistic world, the sports universe reflects and maintains this violent misogyny, and cis men continue to benefit from that. When cis women push the boundaries of this system by excelling in competition, their accomplishments are suspect, they are subject to scrutiny—and some are forced to prove their gender.

It’s not surprising that this atmosphere has generated movements for greater equality; however, we are not all on the same side.

We are beginning to talk about the intersection of sport and violence against women. We are starting to advocate for safe spaces for athletes and fans of all sexualities. These movements are necessary, encouraging, and are long overdue.

But the discussion of gender and sport too often reflects a cisgender world that refuses to acknowledge the abundant variations of trans identity. Gender inclusion in sports is a topic that’s centered on cis women. It’s one that needs to happen. We need more attention, more analysis, and more financial support for women’s sports, especially at the professional level. However, that conversation must broaden to include all athletes and fans of every gender, and agender identities as well.

Trans athletes and trans fans are still waiting to be acknowledged.

What that waiting increasingly looks like is: Wait your turn. Wait until the NHL has a comprehensive strategy to combat domestic violence and sexual assault, and a clear policy to address players who cross this line. Wait until the NHL has one or two (or even a legion) of openly gay players on the ice and several openly gay executives in the press box. Wait until these worthy goals, with their wider impact, are achieved.

Wait your turn.

For trans people, there’s more at stake than just winning and losing. Our identities and our lives hang in the balance.

These issues don’t need to be addressed in some order of their arbitrarily predetermined worth. There is considerable overlap in experiences of racism, religious discrimination, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia in sports. To fully address racism, we must combat homophobia as well; to rid hockey of sexism, we must see the transphobia that intersects with such gendered discrimination. But we also need to see that transphobia is real, that it exists in our game and society, and that it hurts people daily.

Trans athletes and fans aren’t waiting for cis help that might never come. They’re playing and watching and participating in sports now.

Sporting bodies at every level are being pushed by trans kids, trans teens, and trans families, as well as by trans athletes who hope to keep playing, to truly make sport gender-inclusive. There are some wonderful examples of trans kids being welcomed in youth sports or on their high school teams. These athletes should be celebrated and these stories should be amplified as narratives that involve trans people and that do not end with discrimination, violence, or even murder.

But what happens when trans kids grow up and want to keep playing?

For trans people, there’s more at stake than just winning and losing. Our identities and our lives hang in the balance.

Title IX is out of date. Canadian Interuniversity Sport (CIS) guidelines are locked in a traditional gender binary.

When we talk about gender equality, what we’re talking about is a cisnormative understanding, a cisnormative binary. We’re talking about a traditional understanding of gender as male and female—but this knowledge is deeply flawed.

Despite the visibility of a few trans celebrities and athletes, gender is still binary in both our society and in our sports. Most of the time, cis people simply do not see trans people, or fail to recognize and acknowledge our lives as legitimate. When institutions try to be inclusive without consulting trans individuals, they fail miserably.

The NCAA has had its transgender policy (linked above) in place for several years. While three transgender student athletes were consulted and several LGBTQ advocacy groups were involved in coming up with the NCAA’s policy on transgender athletes, the process was also heavily influenced by medical professionals; many trans people find this to be a group that has dubious credentials in this area. I don’t know how much influence the trans student athletes had in the policy creation process, but I do know that the rules produced that address the "complexities of the transitioning student-athlete" are based in a fundamentally cis understanding of gender as a binary.

Transitioning is a process that takes many forms. There is specific terminology associated with it (social transition, medical transition, FTM, MTF), but these terms in no way define the transition process for all trans people. Transition can describe the process of changing from assigned gender to a true identity, but it can also be a state in and of itself.

Some people who were assigned male at birth are women. Some people who were assigned female at birth are men. Some are trans women and trans men. Some are trans, non-binary, transfeminine, agender, androgynous, bigender, genderqueer, gender fluid, or identify with a third gender. Trans identity is highly individual. Trans people exist outside the conventional gender binary. Trans people are also men and women. Trans identity exists in infinite variation.

Acknowledge that variation. Accept that variation. Respect that variation.

The NCAA and CIS don’t. The NHL doesn’t. I hope, but have little faith, that the CWHL and NWHL will. Most CWHL and NWHL players have matured in the NCAA and CIS systems that either didn’t acknowledge trans student athletes during the players’ time at university, or they played under current, cisnormative NCAA rules on trans athletes.

The NCAA policy uses language that exclusively defines transgender in terms of male and female. The NCAA requires proof that trans women have undergone hormone therapy for at least one year before they are allowed to compete on women’s teams. Requiring a specific medical treatment to have your identity respected and to allow you to participate as a student athlete isn’t inclusion or equality. Trans men who are not undergoing hormone therapy can play on either women’s or men’s teams. Trans men who play on men’s teams but aren’t undergoing hormone therapy do not disrupt the team’s status as a men’s team, because women can play on men’s teams. As a result, the NCAA policy does not see trans men as truly male and does not acknowledge their athletic ability as competitive.

Note that under this policy, there is no room for the non-binary athlete. When institutions or individuals refuse to acknowledge certain trans lives, they show that what they accept is not trans identities, but those people who can fit into established norms. Certain segments of the LGBTQ movement place importance on these established norms and on respectability politics. This has been most plainly seen in mainstream gay support of the equal marriage movement in the United States. The message generated is that gay and lesbian couples, especially white couples, are just like their cis, straight neighbors. But for some trans people, this situation proves to be unworkable. For many of us, the reality is that we are not just like you; we are different in important ways and we’re unwilling to jeopardize our wellbeing to fit your norms. The NCAA doesn’t see that.

Aspects of the NCAA guidelines address concerns that trans women will have an unfair competitive advantage over other women in competition. It’s the trans panic defense in another form. This is the mentality that allowed bigots in Houston to undermine and overturn legislation that would have protected trans people (and specifically trans women) using the public bathroom that best corresponds with their identities. It’s the mentality that allows those who murder trans women to use the trans panic defense and be convicted of lesser charges in all US states (except California). It suggests that trans women are shocking, freakish, and deviant; that they are really men who are actively trying to harm women. In reality, it is trans women—and especially trans women of color—who are most often the recipients of contemptible behavior and violence from those around them. Where is the competitive advantage of being continually marginalized and discriminated against?

Sport has a conventional methodology for achieving social change. We are still looking for the minority player-savior. Today’s incarnation is the white, cis, gay player. Black gay athletes and lesbian players exist and are out, and yet we are still looking for firsts. The NHL is still looking for its first openly gay player, and a recent Pierre LeBrun interview with You Can Play founder Patrick Burke is illustrative of the importance of the savior model to our understanding and acceptance of minority athletes. If we only had one openly gay NHL player, we muse, we could take the next step in gay rights in sports. If we only had one openly gay NHL player, we could instantly rid hockey of homophobia.

It’s a pattern that’s historically been used in sports, but it seems particularly outdated in 2015. The question the LeBrun interview fails to ask is what we can do, as hockey fans, to cultivate an atmosphere of tolerance and acceptance in sports culture for gay athletes. We need to create an environment where an athlete feels safe coming out, but we also need to create an environment where an athlete doesn’t feel pressured to come out to ease fan and league concerns about the accepting and progressive culture of NHL hockey. LGBTQ people don’t owe you their coming out stories and they don’t owe anyone their private lives lived publicly. It’s 2015: the responsibility for change shouldn’t be on the one, but the many.

Participation can jeopardize safety if it leads to being outed, and for many, it’s not worth the risk.

If we follow this pattern, we’ll be waiting a long time for a trans player-savior. There have been trans athletes who have played competitively and successful athletes who have since come out. But the system is stacked against trans athletic success. Trans athletes still face considerable barriers in youth sport. Participation can jeopardize safety if it leads to being outed, and for many, it’s not worth the risk. Lots of trans athletes lack the necessary economic resources to participate in sport at a high level. Trans people have additional barriers to accessing higher education and consequently face further obstacles to higher quality of competition.

We shouldn’t be looking for a trans player-savior. The player-savior does give us courageous athletes who are worthy of veneration, but it takes too great a toll on individuals. Too often, the player-savior is sacrificed for the cause. The hockey community can make the necessary changes to make our sport more inclusive by asking how can we, as a community, create safe environments for the LGBTQ community?

My answer is simple: we cannot have trans acceptance and trans safety without disrupting and dismantling the traditional gender binary.

There are ways to do this in terms of hockey. Support women’s hockey. Watch and read about women’s professional hockey leagues, like the CWHL and NWHL. Follow women’s international hockey and not just the North American teams. Attend women’s college hockey games. At the highest levels, women’s hockey challenges traditional gender roles, as well as the depictions of women who love hockey that come from mainstream sources, such as the NHL. The more we see elite level women’s hockey, the harder it is to classify the sport as solely a "man’s game."

Support and advocate for mixed-gendered sports. Tennis has had mixed-doubles events for years. Mixed-doubles curling has a world championship, major bonspiels, and will be a full medal sport at the 2018 Winter Olympics. Pairs skating and ice dance are popular figure skating events. Downhill skiing has mixed-gendered team events on the World Cup circuit, and cross-country skiing has a history of mixed-gendered events and seems poised to restore these contests. Biathlon has a single-mixed relay and a double-mixed relay event on the circuit. Ski jumping mixed team events have been proposed for the next Winter Olympics. Both the bobsled and cycling federations have interest in mixed events for the 2018 and 2020 Olympics, respectively.

We should enthusiastically support these endeavors and push for "mixed" to truly mean all. Men and women can be teammates and compete against each other; it’s cisgendered indifference that prevents non-binary athletes from being allowed to participate in these competitions. Cisnormativity is stopping sports fans from pushing for this type of integration in more sports.

We should also push recreational leagues, kids’ leagues, high school leagues, college organizations, and professional sports to update their gender guidelines. In some cases, like the CIS, organizations need to be forced to acknowledge all athletes. Sporting bodies like the NCAA need greater trans inclusiveness, especially for non-binary athletes.

What does a better trans inclusive gender policy look like? It looks like US Quidditch’s wonderfully named "Title 9 ¾". While the wording in any guideline can always be improved, Title 9 ¾’s "four-max rule" is drafted so that non-binary athletes are welcome by allowing all players to self-identify and recognizes that some athletes do not identify as female or male. This is the direction that all sports need to follow.

Those are significant steps to take, but they’re collective steps. Individuals in the hockey community can take action, too.

You can call out NHL players who make transphobic remarks on Twitter and step up where YCP has failed. You can challenge fans with transphobic Twitter handles and transphobic blog names to consider the message that they send to both trans and cis hockey fans alike.

You can reflect on how the media that you think is "just entertainment" impacts trans safety, especially when trans folks mention that your favorite sports blogs and websites contribute to transphobia and the violence that trans people experience. In short, you can take some of the steps you might already take to combat racism, sexism, ableism, and homophobia. Be mindful of the ways these forms of discrimination interact and overlap.

For the trans lives that are in jeopardy, the urgent nature of the threats we face requires an equivalent urgency on the part of cisgender people who both control and consume our current sporting culture.

Most importantly, listen to the people who experience the trans reality daily. Listen to trans women, those who are feminine-of-center, those who are non-binary, those who are transmasculine, and trans people of color.

A trans-inclusive culture and sports landscape will look drastically different from our current examples, but it’s a change that can’t come soon enough. When sport is safer, more accepting, and more inclusive, society is correspondingly less dangerous. For the trans lives that are in jeopardy, the urgent nature of the threats we face requires an equivalent urgency on the part of cisgender people who both control and consume our current sporting culture.

(Photo credit: Bob Walker/Flickr)