This is Part 2 of an informal series we are doing this summer about officials in women's ice hockey. Part 1, on how the pro leagues are expanding opportunities for officials, is here.

Krissy Morrison wants to officiate in the Olympics. In order to reach that goal, she has to become the best official she can be. She has to work a ton of games and she has to be used to the physicality and pace of high-level play. She has to reach the pinnacle of her own trade in the same way that the athletes do.

And she can't do that by officiating women's college hockey.

Morrison is one of the best female officials in the country. She followed her father's skate tracks and began officiating at the age of 10. She advanced to working DI and DIII college games after completing her own playing career in 2005. But she's never officiated at the Women's Frozen Four.

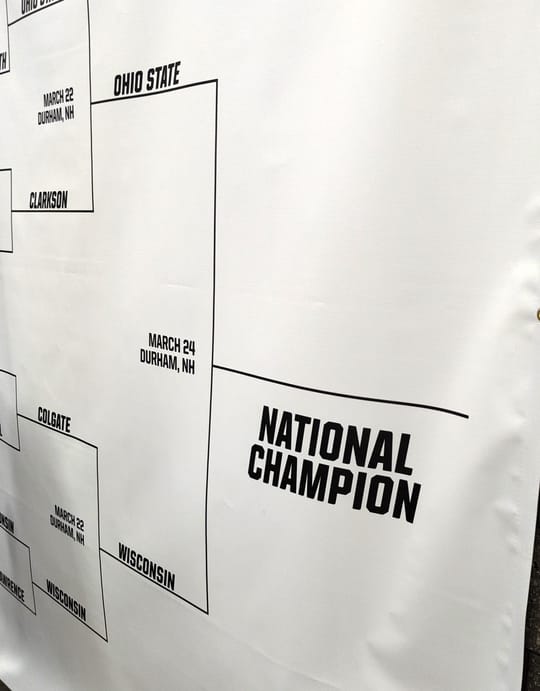

NCAA rules require that the officiating crew at the Frozen Four not have any affiliations with the teams that are playing. Unfortunately for Morrison, there has never been a national championship game that hasn't involved a WCHA team. As a result, even though she's widely regarded as one of the best officials in the women's college game, she doesn't have the national championship on her resume.

There's a ceiling for how high she can go.

One does not play Division I hockey without having a competitive instinct, and that drive, that passion, does not disappear just because the player graduates from college.

Morrison found that officiating fulfills what was missing when she was done with her college playing career. It was competition that led her to start officiating when she was 10 years old.

"My dad and older brother had already been officiating for a couple seasons, and we saw it as a great opportunity to get more ice time and see the game from another angle. It just so happens that my brother and I were very competitive. When I was old enough, I couldn't wait to try and do it better than him!" she said.

That competitive streak has only grown as she's gotten older. The goals may be different, but the passion and drive are exactly the same.

Having felt confident that she had reached her threshold in the women's college game -- but knowing that she still wanted to reach her goal of officiating at the Olympics -- Morrison was forced to reevaluate.

While other conferences do allow officials to move between the men's and women's game, the WCHA does not. They keep two separate pools of officials from which to draw. In order to continue to grow as an official and pursue her goals, Morrison left the women's side and spent the 2016-17 season officiating men's WCHA games.

She had come to the conclusion that moving into the men's game could help provide her with the opportunity and growth that she was looking for.

"I selected the men's side with goals to gain a new experience, be a pioneer, and face a new set of challenges," said Morrison.

While in some ways Morrison felt like she was moving away from the game she loved, she knew that the move to officiating on the men's side was ultimately what was best for her, personally and professionally.

"Most officials that I work with are aware of my deep passion and support for women's hockey. It was a very difficult decision; however, an essential one the season before the 2018 Winter Olympics. The Winter Olympics is my ultimate goal and dream. Every time I get on the ice, this goal is on my mind. Let's be honest, every day this is what is on my mind," she said.

Katie Guay has broken numerous glass ceilings as an official. She's the first woman to regularly work men's Division I games. She was part of the first female crew to officiate a game in the SPHL, and last season she officiated numerous men's games at Madison Square Garden.

"I think if you had asked me some of these questions before last year, I may have given some different answers. But now that I've done some men's games, my perspective has changed," she said. "I think now having had some games last year and this year under my belt, as an official, we're just trying to work the highest level possible. To be able to go out there and be in a high level game, that's only making us better officials. To be in that atmosphere makes you an all around better official. Hopefully that's what I gain from the experience doing these men's game and continue to improve across the board."

Too often, officials assigned to the women's game are ill-prepared, whether because of a lack of overall experience or a lack of knowledge of the women's game. Someone who's familiar with the men's side often struggles with a women's game, Guay said, because there's so much gray area. What constitutes a body-check and what is just contact?

"At the end of the day, [we] just want the best officials on the ice. I don't think it's necessary to have women out there, but it's great for the game. Having women out there doing a great job is encouraging. It's good for the sport," she said.

And while we continue to see increased parity in the women's college game, Guay said there are still plenty of games where a talent gap exists.

"I think one of the hardest parts of the women's game is officiating a very strong, skilled team against a little bit of a weaker team. You get the same exact type of contact, the same level of contact over the course of the game. You don't want to penalize the stronger team for being stronger just because a player is falling down or on the ice," she said.

That's the gray area where Guay thinks it's so difficult for officials not familiar with the women's game to parse. Having played herself and having officiated so many of these games in the past are a huge advantage for her, she said.

The best officials are experienced, but there seems to be a gap between the number of officials who work at youth and high school games and those who go on to be qualified to officiate at the college level. Guay has a full understanding of this gap.

"Doing a youth game and a high school game are so mentally challenging as an official. With the parents and coaches that are very, very vocal, if I'd started as a kid, I'm not sure I would have continued," she said.

But at the collegiate level, there's a lot less yelling from the seats and a lot more professionalism on the ice. An official has to survive the youth level to get there, but if they do, it's a much better environment. At that level, the possibilities seem almost endless. The growth of the sport has brought a wide array of events, leagues, tournaments, and special events that are just as exciting for an official as they are for the players.

Guay said that she continues to be offered new opportunities, ranging from the Beanpot and the outdoor women's game at Fenway Park to international tournaments, which is something that has helped feed her hunger.

"When I first started, my goal was to do an international tournament," said Guay. "To be able to officiate different levels across the globe and be able to meet hockey people has been a great opportunity and has sort of kept me in the game," she said. "To be able to have these opportunities sprinkled in -- the goals just kept elevating. As an official, you want to be out there in the big games. And as I was given some big games one year after another, I just wanted more. Having those opportunities that I've been given so far have kept me excited."

Guay is quick to point out that though she has been given the opportunities, she's not the first woman capable of officiating at those different levels.

"I think there are many female officials before me that could have gone down there and done a game [in the SPHL]. The opportunity wasn't there [for them]. For this to happen, it was great to have that opportunity and open eyes. It's great for little girls in the stands. I don't ever remember seeing a female official on the ice growing up. I think for the youth to see women in different roles, having role models in different areas of the game is going to grow the game at all levels," she said.

"It's definitely an honor, but there's definitely many females that certainly could have done the job as well. The time has come where I've been given the opportunity at the right time," she said.

"Just to be out on the ice versus behind the bench, the adrenaline flows like it did when I was a player. I have the best seat in the house and I'm getting paid, what could be better?" said Guay.

Morrison and Guay are pushing the boundaries and creating a new normal for female officials, but sadly, they are still a rarity.

The four women's college hockey conferences reported a total of 235 officials having worked women's games for them during the 2016-17 season.

Of the those 235 officials, 32 were women.

According to a 2011 ESPN article, there are roughly 2800 registered female officials in the United States. According to USA Hockey, they have roughly 24,000 registered officials.

In May, Melissa looked at the state of officiating at the professional level and noted how often female officials took the ice. That happens far less frequently in the college game.

While international hockey requires a full crew of female officials, with just 32 women nationwide who are currently officiating women's college hockey, it seems unlikely that we'll see a full female crew officiating at the national championship any time soon.

Dave Lezenski, Hockey East Supervisor of Officials, is proud of his league's efforts to get more female officials on the ice.

"I think that we have an obligation to recruit and attract more female officials," he said.

To that end, he and representatives from the league talk to each team in their conference to try to convince the student-athletes to try officiating. One of the biggest barriers to officials moving up to the college ranks is their speed and skating ability. In recruiting alumnae, conferences can ensure the officials are strong, quality skaters.

Steffan Waters, Director of Communications for the CHA, said the conference is taking steps to add to their officiating pool.

"We, as a league, are working to recruit more officials, especially women to be a part of our officiating team. [We are] holding meetings at DIII schools, telling our DI players of opportunities after they're done playing, and running camps in various cities around the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic," he said.

Hockey East representatives attend officiating camps all over the east coast, Lezenski said. "We'll go anywhere to find an official."

One recent success story has been Dana Trivigno, who brings an interesting perspective as a recent college graduate who's playing professionally and is just starting out in her collegiate officiating career. Lezenski described the Hockey East officials as a family and Trivigno said having that network of support and knowledge has been helpful.

Though she obviously had ties to Boston College, she said it hasn't been difficult to transition to the other side of things on the ice.

"Obviously there are a lot of familiar faces. I try to keep it professional as much as possible. On the ice, it's kind of all business. It is a job. I am getting paid to officiate and the game means something to everyone involved. I owe it to them to be professional, to be unbiased and to give it my all," she said.

Lezenski said he had no qualms about putting Trivigno -- or any other former player -- on the ice of the league they'd just left.

"Character is important as an official. Integrity is important as an official," Lezenski said. "I've got too much integrity to put someone on the ice that's going to lean towards one side or the other. When you step on the ice, everything else goes out the door."

Trivigno is the only one of the three women interviewed here who is still actively playing at a top level, and she said officiating has definitely helped her in her own game. As a professional player whose calendar is constantly in flux, officiating also provides her with an incredibly flexible job. She's in control of telling Hockey East when she's available and when she's not, and she can work around her own games in the NWHL, which makes officiating a near-perfect job for her at this point in time. Not only is the job fun (something she said she thinks people overlook), but it also has helped her become a better player on the ice.

"The biggest thing that I've seen from being a linesman is that there's so much open space. Sometimes as a player, when you get the puck, you look up and you feel like you don't have any time. Now that I've seen it on the ice, but as a third party, There's so much more space and time than you think. I've tried to incorporate that into my game. It's easier said than done. It's definitely given me a new perspective on the game," Trivigno said.

Though Trivigno is certainly an example of recent recruiting success, she's the exception, not the rule.

The directors and supervisors of officials for each of the conferences spoke of the need for more qualified, well-prepared, and committed officials, though none seem to have any formal protocol or programs for increasing their numbers.

Morrison is passionate about not only the need to recruit more officials, but the need to do so in a thoughtful and productive manner.

"Who are we recruiting, what type of support do they have, and how to retain them?" she said.

As both Guay and Morrison spoke of the impact of their mentors in their career, it's clear that having leadership, support, and guidance were all crucial to their advancement as officials.

Morrison would love to see a better partnership between the officiating community and the coaching community, where coaches are identifying prospective officiating candidates, providing information and contacts to them, and helping to plant the seeds of moving into that part of the game.

Though recruiting former collegiate players is one path, Morrison would like to focus on growing officials from the youth level. She's seen many officials who start young fail to advance for a variety of reasons. She wants to see better focus on support and retention at the younger ages to ensure that prospective officials complete their training and testing, and that they aren't chased away by bad experiences with coaches and fans. She's got a clear idea of the need for mentorship and guidance that keeps new and young officials engaged, supported, and validated while growing themselves in this new role.

To be capable of officiating at the DI level takes a lot of work, both on and off the ice. USAH's numbers show that there are numerous registered officials, but that number dwindles significantly at the DI level. The conference heads of officiating are not willing to jeopardize the integrity of the game by advancing officials who may or may not be prepared for that jump.

It's a commitment, for sure, but it's one that has to be shared. The individual officials need support from their local hockey associations and supervisors of officials. Those leagues and state associations need support from USA Hockey. All of them must work together to make a commitment to grow this side of the game.

Would that officials and supervisors in all cities and states and at all levels of the game were as impassioned and committed as Morrison and Guay. The path forward is clear, especially with more opportunities coming in the professional leagues for women officials to get more experience with the world's best players. But with no clear, concise, or unified commitment to recruiting at youth and college levels, it's unlikely that there will be changes in the number or quality of officials for the women's game any time soon.

(Photo credit: Katie Guay/Twitter)